// Foreword

[Spoilers for The Boy and the Heron and How Do You Live]

Why do we create?

For fun? To better understand ourselves? For Profit?

Our minds are wonderful things.

But for all their wonder, I often think that they greatly outclass the rest of what us humans are left to work with.

Like all the explosive energy of the sun being compressed down, refined, simplified, and converted into a mere trickle hardly powerful enough to charge your phone, I often feel a similar disappointment when the simplicities of our tools and languages cannot express the fusion-like abstractions our minds are capable of.

In an instant, you can know exactly what you want to say. The next, not be able to string together the words to properly convey that feeling or concept.

To quote the book that started it all, “He had all sorts of feelings, but when he tried to write them down, somehow, they wouldn’t come together. Before Copper knew it, his thoughts had left the notebook and wandered off toward the kitchen.”

Sometimes, with effort and care, you can distill this mess into one clean idea – one execution with a beginning, middle, and end, all wrapped up in a bow.

Sometimes, you cannot. Sometimes, it’s more complicated.

You’ll sit, staring at the empty page as the ideas swirl around at light speed. You perfectly understand them all, yet they elude you entirely.

You’ll finally get out a sentence or two. Hmm, not quite right.

If you work at it long enough, you might get something.

Sometimes, you get an abstraction; a pasta nest of ideas that connect at times, and others not at all. From the outside it looks like one thing, but as you unravel it, you realize it’s something else entirely. Maybe it’s multiple things.

If you’re willing to take the time and dig deep, sometimes you can get something amazing.

A beautiful supernova of self-expression that cannot be understood by trying to follow it from A to Z. A magnum opus from a legend who has dug deeper into himself than ever before.

This is The Boy and the Heron.

// The Boy, The Heron…

The Boy and the Heron takes some inspiration from the book How Do You Live, but it is not a straight adaptation. This is also likely the reason it was released as The Boy and the Heron, as opposed to keeping the name How Do You Live like it has in Japan.

We’ll get into what exactly it takes from the book a little later.

The Boy and the Heron checks all the usual Studio Ghibli boxes. It has funny old ladies, it has honkin’ noses, it has cute little guys – they’re all here.

These things don’t feel as though they are simply repeating the same idea over and over again, rather, this movie feels like it’s paying homage to the Ghibli library – to Miyazaki’s life’s work.

The movie begins with a war siren and a very intense scene where Mahito learns his mother’s hospital has caught fire. He quickly dresses and tries to go help her.

These scenes are animated with a haunting beauty. People clog up the streets, illustrated as stretched out eerie visages of who they might otherwise be, swaying and warping around Mahito as he runs through the street as if personifying the very smoke filling the night sky.

His mother does not survive, something that Mahito still suffers from three months later. We also learn that his father has since got together with Mahito’s aunt, AKA, his dead wife’s sister. He certainly wasted no time.

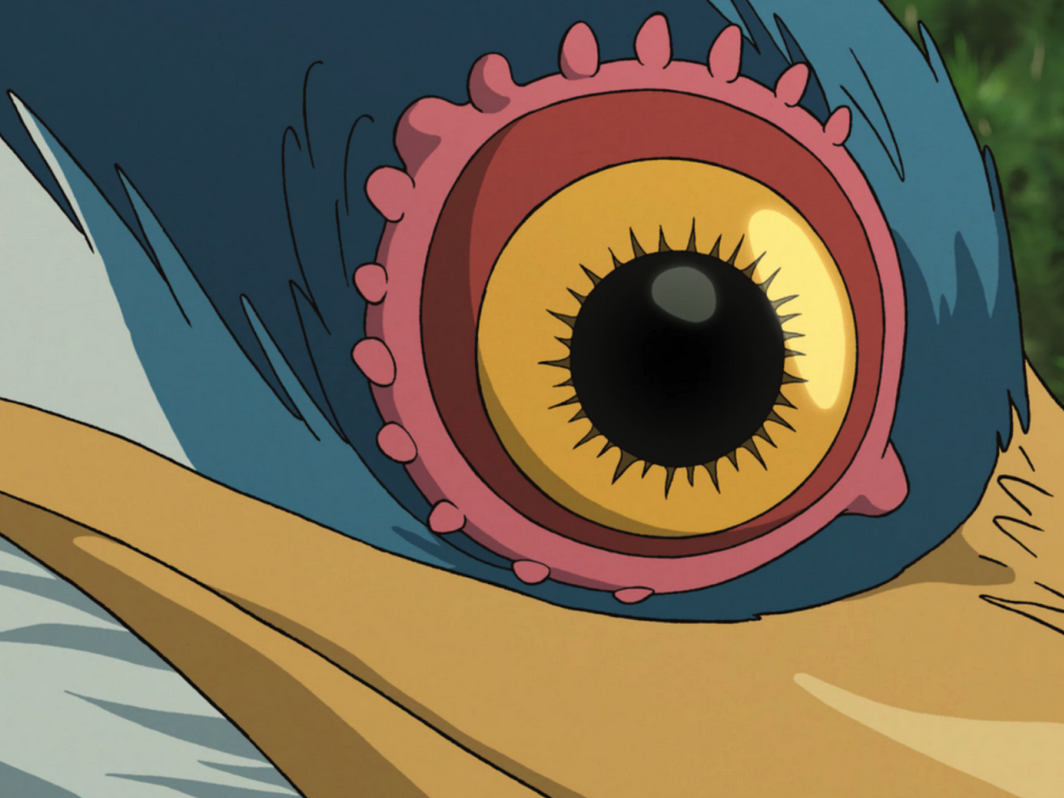

They arrive at the remote countryside house that is brought to life with all the quiet whimsy Ghibli has so carefully mastered. It’s not long – however – until a strange heron begins harassing Mahito.

The first half of the film takes place at the countryside house. It is with great restraint and patience that Ghibli masterfully executes what is most likely the quietest and slowest segment of movie in their library.

The pacing is slow but deliberate. Many scenes are executed in complete silence, with little dialogue. This makes it all the more meaningful when the heron shows up, and we’re met with a few chilling, simple notes on the piano.

While the movie doesn’t go full A24 (it does have to maintain a PG-13 rating) I was always left with a tingling in the back of my mind that we were building to something. A sense of unease buried beneath the usual Ghibli splendor.

I was absolutely glued to the screen during this part. Every background is a stunning painting. Mahito is brought to life by absolute masters of their craft, animating him with so much subtle yet lifelike detail. Whether that be him crawling around the top floor after he sneaks out of his room at night, or hopping and shuffling along as fast as he can to get dressed in the start of the movie. Not one frame of animation in this movie is “default.”

Interactions between Mahito and the heron escalate, and he finds himself brought to a strange, magical land. It’s here that he meets a colourful cast of characters, many of which have a connection to someone in Mahito’s world.

The colourful cast, I might add, contains many actors from previous Ghibli works. Willem Dafoe, Christian Bale, and Mark Hamill contribute to the all star cast. They’re joined by Miyazaki newcomers like Dave Bautista, Gemma Chan, and Robert Pattinson.

More than anyone, Pattinson stole the show here as The Heron. It’s clear he’s left his “The Guy From Twilight” title behind, but who knew he’d leave it this far in the dust. I’m not alone in saying that I was legitimately shocked at how impressive his voice work was here. This is exemplified by the fact that it came totally out of left field.

I certainly hope we see more of Rob in the VA scene.

Mahito explores this new world, much of which neither he nor the viewer will fully understand. This all culminates in him meeting the tower master, a character that we will dive into further in this breakdown.

The Boy and the Heron has been described as being, “less approachable,” than a lot of the other Ghibli movies. This is understandable. As I mentioned in the intro, it’s not necessarily a tale that takes you from A to Z. It’s a story that imparts a message.

It more or less gives you a bowl of alphabet soup and invites you to slurp up the parts at your leisure. You can tell they are from the same soup, all contributing to a larger idea, but they don’t string together a sentence.

And that’s by design.

// …and Beyond

It’s no secret that this is one of Miyazaki’s most autobiographical stories.

Let’s get into that, starting at the end.

In the finale, Mihito is offered the position of tower master from his great uncle. He declines, as he has his own life to live; he has his own friends to make. This is the beginning of the end, and the world begins to crumble in the wake of the Tower Master’s efforts disappearing.

Could this be Miyazaki’s externalization about his thoughts on the potential future of the studio once he is gone? An old man struggling to hold together this world of beauty, all too aware that his time is ticking away. Miyazaki has undoubtedly created a new world – he’s created many – and he still works tirelessly to keep it alive.

The world is destroyed. The beauty of it, torn and crushed as it collapses without its once great master keeping it stable. By the end of the film, it lives on only in the minds of those who were there to see it. But this is just one of many worlds.

It’s undeniable that this is analogous to Miyazaki. Knowing that he made this for his grandson to remember him once he’s gone makes it all the more bittersweet. It also imparts the message: Live your own life. Be your own person.

This is despite all the masses who are upset at the loss of something they hold so near and dear: the bird people in the movie, and the fans (you and I) in real life.

The most cynical might note that the Tower Master skips a generation, going for his grand-nephew. Perhaps, he was not confident in his daughters’ abilities. Perhaps they tried once and failed.

*cough* Gojo *cough*

While the tower master might be the most obvious analogy for Hayao Miyazaki, a lot of Mahito’s life was inspired by Miyazaki’s as well.

Mihito loses his mother, as mentioned earlier. Miyazaki also lost his mother, and had to flee a city because of an impending war. His father also worked in aircraft manufacturing.

The characters of the heron and the tower master were both revealed to be inspired by Isao Takahata and Toshio Suzuki, the two individuals who founded Studio Ghibli with Miyazaki.

Having the tower master not only represent Miyazaki, but what someone else meant to him, is the perfect example of the nebulousness of this movie and its themes.

I believe there is even more messaging to be found in the way The Boy and the Heron portrays Mahito’s mother. Not his dead real-life mother, but the mother in the fantasy world.

Mihito comes into contact with an other-world version of his mother, who is in the form of a girl about his own age. I believe their relationship is representative of both his relationship with his own mother, and the relationship he hopes to have with his grandson.

Nearing the destruction of the world, Mihito wants his mother to come back with him. She rejects this idea, saying that he needs to go stand strong on his own.

This not only offers Mahito some much-needed closure for his mother’s death, but reinforces one of the central messages of the movie:

It’s hard to lose something you care about! The bird people were upset at the loss of their world, just as Mahito was upset at the loss of his mother, just as you and I will be upset when the day comes that Miyazaki does actually stop making movies.

One can know no suffering without knowing joy. This in turns makes the act of suffering something uniquely human; uniquely something experiential that only those capable of appreciation can understand.

As the book How Do You Live would illustrate, few would lament the lack of being King unless they had known what it was like to sit atop a throne previously. One would not despise having only two eyes instead of three. They might, however, should they find themselves with only one.

This is one of many lessons the book gives us that are on display in the movie.

Speaking of which, what’s up with the book?

// How Do You Live?

It wouldn’t be a proper analysis without comparing it to the material that this film draws its inspiration from. The book which carries the same title as the movie in Japan, How Do You Live, was written in 1937 by Genzaburo Yoshino.

After seeing the movie for the first time, I had to know more about the book. I knew nothing about it aside from the fact that the book was literally in the movie at one point.

That’s about the only tangible connection between the two. Beyond that, it’s simply the themes and messages that Miyazaki drew inspiration from. “Drawing inspiration” might not even be the right way to put it. I think he was inspired by the impact of this book, and that is what he has tried to do with The Boy and the Heron.

The book features a young boy named Junichi Honda, nicknamed Cooper. He lives with his mother. Although his Father has died, he is very close with his uncle. The story follows Copper as he goes through the ups and downs of being a first-year junior high student.

It alternates between Copper’s experiences and the lessons he learns, and reading through a journal his uncle is writing for him. His uncle teaches him new things and gives insights into what Copper says and does.

The book teaches philosophy, history, religion, and sees Copper having some very realistic existential eye-openers that seem to perfectly match how it felt to be a young boy having realizations about the world.

It’s truly a coming of age story. Its pages impart all kinds of thoughtful lessons on the reader about the best ways to contribute meaningfully to the world around them. It’s been studied by children in Japan, and is a favourite of Hayao Miyazaki.

What I was most surprised by was its timelessness. Its messages about the worth of a person being what they choose to do with their life over how wealthy they are is as poignant as ever. Its lessons about the history of Buddhism were still interesting today. Its insights into the global supply chain and the almost inconceivable effort that goes into every product you see still rings true.

It’s very easy to forget this book came out almost 100 years ago.

It’s not hard to see how these themes align with the movie.

When Mihito finds the book left behind by his mother and reads it, it has a profound effect on him. Up until this point, Mojito has shown us that he is relatively selfish. He injured himself to get out of school, causing everyone to worry about him. He begrudgingly visits his sick aunt only after numerous requests to do so. Even then, he quickly leaves and steals her cigarettes.

Him reading the book is really a turning point in the film. The first thing we see after this scene is him rushing out to help find his aunt with a newfound sense of purpose and caring. It is also literally a turning point because it’s just before he travels to the new world through the tower.

The book’s themes were a driving force for the movie, and Mihito’s character.

It is with perfect synchronicity that these themes transcend the novel, the film, and the real life meaning Miyazaki hopes to impart on his own grandson – and all of us.

// Conclusion

Why do we create?

For fun? To better understand ourselves? For Profit?

Yes, for all of these reasons and more. But there is one reason for creation that produces the most incredible results: When you create because you have to.

When you have an idea or a passion that is so hot you can feel it burning in your mind. An unquenchable urge that will never be satisfied until the story is told – until the art is expressed.

Something so powerful that you wonder how it had been kept locked up in the creator’s mind all this time.

The Boy and the Heron is Hayao Miyazaki laid bare. It’s his love, fear, past, and future all in one. It’s confusing at times, yet simple at others. The film’s ideas orbit in and out of each other’s gravitational fields, at times even colliding.

We can see how Miyazaki is injected into the movie at every level, even at times when others are also there. He’s many strings near but not touching, all vibrating at a harmonious frequency.

This movie *is* Hayao Miyazaki.

With it, he imparts on us wisdom, thoughtfulness, direction, and inspiration. He leaves this film behind as a memory to be cherished, and as a swift kick in the pants to remind us not to spend our time stuck in the past.

He encourages us to become producers – creators of our own magical worlds. To love what is there, but to love even more the unimagined possibilities yet to be.

With this film, Miyazaki asks each one of us: How will you live?

Pingback: GCR Oscar picks – GCR